C101: The Puppet Master’s Origin Story

The making of a mastermind in a fractured land

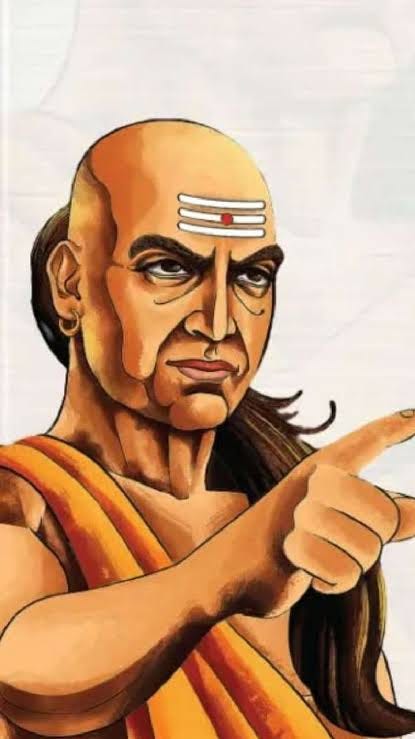

Happy Thursday! Just two more days to the weekend. The markets have calmed down just a little, so I thought I would sneak in a Chanakya post before we all get whiplashed by Trump, China, or another Deep Seek. If you missed it, I introduced Chanakya briefly here. I will keep taking such breaks from writing about macro to return to Chanakya - a cold, clever, unrelenting scholar-strategist who mentored a kid into toppling a dynasty.

In the late 4th century BCE, India was a patchwork of fractious kingdoms, where power shifted like monsoon sands. At its heart loomed the Nanda dynasty, ruling from Magadha in the east—a realm rich in rice fields and war elephants, yet rotten with excess. Into this world stepped Chanakya—known also as Kautilya—a figure whose life straddles history and legend, the architect of the Arthashastra and the mind that forged the Mauryan Empire. His story begins not with a crown, but with a slight that sparked a revolution.

Who was this man? The Arthashastra offers no autobiography, but later texts like the Mudrarakshasa and Jain traditions sketch a portrait: a Brahmin scholar, wiry and sharp-eyed, born perhaps in Taxila or Pataliputra around 375 BCE. His teeth were crooked, his temper fiercer still—a man of learning who’d mastered the Vedas, logic, and politics. What drew him to the Nanda court? Some say intellectual hunger—Magadha’s capital was a hub of debate, its king Dhana Nanda a patron of sorts. Others argue ambition: a young Chanakya seeking influence in a kingdom flush with resources but teetering on arrogance.

The Nandas were no petty tyrants. By 326 BCE, when Alexander’s armies stalled at the Hydaspes, Magadha boasted an army of 200,000 infantry, 20,000 cavalry, and 2,000 chariots—numbers from Greek accounts that dwarfed most rivals. Their wealth flowed from fertile Gangetic plains and trade along the Uttarapatha, a highway linking India to Persia. Yet their strength masked rot: Dhana Nanda, the last of his line, was a miserly hedonist—Plutarch calls him a king who hoarded gold while his subjects grumbled. Corruption festered; nobles schemed. It was a regime ripe for upheaval, much like the Ottoman Empire in its waning 19th-century days—formidable on paper, fragile within.

Enter the insult. The tale varies: Dhana Nanda mocked Chanakya’s gaunt frame, or ejected him from a feast for debating too fiercely. The Vishnupurana claims he tripped over a rug, earning jeers. Whatever the spark, Chanakya vowed revenge—untying his Brahmin topknot, he swore it’d stay loose until the Nandas fell. Was this mere ego? Hardly. A hurt pride might sting, but toppling a dynasty takes more—think of it as Lenin’s exile fueling 1917, not just a personal snub. Chanakya saw a system begging for reform, and his intellect, honed in Taxila’s cosmopolitan schools, craved a grander stage.

Then came Chandragupta Maurya. History knows little of his roots—some call him a Nanda bastard, others a village boy from a Kshatriya clan. The Arthashastra is silent, but later lore paints him young, raw, and fierce—perhaps 20 when Chanakya found him. Imagine a Spartacus figure: bold, unpolished, hungry for more. Greek sources like Justin hint he met Alexander’s scouts, tasting ambition beyond Magadha’s dust. Chanakya saw clay to mold—a warrior to pair with his strategy, the brawn to go with the brains.

Their alliance was alchemy. Chanakya, the theorist, taught Chandragupta war and guile; Chandragupta, the doer, brought muscle and charisma. By 321 BCE, they’d toppled the Nandas using spies that sowed dissent and with the help of tribal allies like the Himalayan Kambojas swelling the ranks of Nandas.

Chanakya’s use of spies is particularly the stuff of legends. Chanakya didn’t just send agents; he wove a web. Picture a merchant in Pataliputra’s bustling market, griping about Dhana Nanda’s taxes—only he’s no trader, but a sanchara, a wandering spy from Chanakya’s playbook. Another, a monk begging alms near the palace, listens as guards curse their stingy king. These weren’t random plants; the Arthashastra (Book 1, Ch. 11) details their training—orphans or outcasts, schooled in deception, slipping into enemy ranks to whisper doubts. One tale, from later lore, claims a fake prophecy spread by such spies convinced Nanda nobles a curse doomed their line. Chanakya was the misinformation-in-chief of his time and he understood deeply the value of confidence (or the lack of it). The court fractured—ministers hoarded gold and generals hesitated. It was psychological sabotage, not unlike CIA-backed rumors toppling regimes in the 20th century.

He was also aided by triable allies that proved to be the Achilles’ heel for the Nanda dynasty. The Kambojas, fierce horsemen from the northwest, had long bolstered Magadha’s cavalry, paid in coin and land. But Dhana Nanda’s greed—skimming their tribute—soured the deal. Chanakya saw the crack and pried it open, offering the Kambojas better terms. They flipped, their lances turning on Nanda outposts. It echoes Rome’s German mercenaries—think Arminius, a Cherusci prince trained by Rome, who betrayed Varus in 9 CE, slaughtering legions in Teutoburg Forest. Trusted outsiders became daggers in the back; the Nandas never saw it coming.

The Arthashastra emerged from this crucible—not a dry treatise, but a playbook forged in revolt. In Book 1, Chapter 7, Chanakya writes, "The king shall employ persons from among his own kinsmen and those of his enemy to test the loyalty of his ministers." This isn’t abstract—it’s a blueprint for rooting out snakes, using insiders to dangle bait like gold or titles, seeing who bites. Book 1, Chapter 10 adds, "He should test their loyalty by means of secret agents with temptations of wealth, lust, and fear." Here’s the method: spies pose as corrupt envoys, offering bribes or threats—honest ministers refuse, traitors waver. Chanakya lived this, sifting Nanda loyalists from turncoats.

Compare this to older history: Thutmose III’s rise in 15th-century Egypt relied on priests and generals, not a lone genius. Or jump forward—Machiavelli’s Prince counsels similar ruthlessness but lacks Chanakya’s granular systems. Today, his shadow lingers in intelligence agencies staging soft coups or even in the US Army (see here) or CEOs pruning disloyal boards. Was it ego? Yes, but fused with a vision: order from chaos, a state ruled by reason, not whim.

The world Chanakya knew was brutal—Alexander’s retreat left a power vacuum, Persian trade faltered, and Magadha’s neighbors eyed its riches. He didn’t just react; he reshaped it. We’ll go further into the unraveling of the Nanda kingdom next time, but I hope you enjoyed this. Nice break from Trump's tariffs, innit?